Historically, in counties such as Brazil, coffee was a majority slave industry. Although today slavery is illegal in all coffee producing countries, it still exists in forms of coercion, exploitation and forced labour in an industry of 26 million people.

In terms of developing country exports, coffee is the second most valuable commodity. The majority of capital is made via the end product, usually sold in the developed world via coffee shops and supermarkets. Due to the volatile price of coffee, there is significant risk of exploitation within the workers’ supply chain, stemming from its original sources primarily in developing countries. Farm owners have no leverage on the commodity price and therefore bear the consequences of price flux, making labourers on their farms the most vulnerable people within the supply chain.

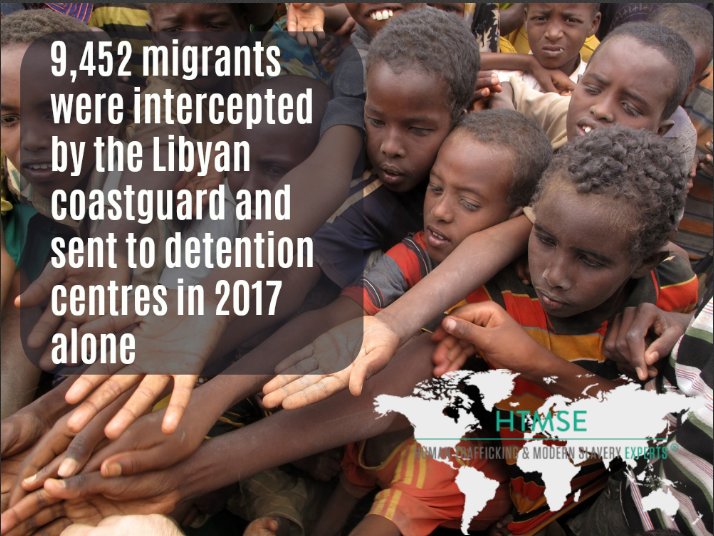

Smallholders produce coffee on farms of less than 25 acres, and have relatively fairer working conditions and more sustainable production. In comparison to Estates, however, they do not have the resources to stay competitive when prices drop despite being responsible for over half of global coffee production. Estates produce coffee on more than 25 acres, and in contrast have economies of scale which do not suffer such consequences of price flux, however tend to be more exploitative than Smallholder farms. Harvesting coffee is a seasonal job, so migrant labour systems have developed (primarily) for Estates, often from poorer and desperate neighbouring regions, which leads to exploitation by farmers. Migrant workers who are extremely dependant on their employers are at high risk of being put out of work when harvest demands.

The major issues amongst coffee labourers tend to be low wages, lack of signed or contracts altogether, dismal living conditions including lack of privacy, safety, sanitation, and adequate housing. For example cases of 40-60 families living together in overcrowded warehouse spaces have been reported.

In 2016, countries that produced coffee using forced or child labour were Côte d’Ivoire, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Guinea, Honduras, El Salvador, Kenya, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, and Vietnam as recorded by the U.S. Department of Labour’s ‘List of Goods Made with Forced Labor and Child Labor’. However, along with the lack of supply chain regulation in this industry, there are limited comprehensive studies done to investigate forced labour. A 2012 report in Peru found that Fairtrade coffee did not produce a higher standard of work for farmers. In 2014, a study within Uganda and Ethiopia suggests the agricultural labourers of Fairtrade coffee had lower wages and living standards than non-Fairtrade labourers. The most extreme example is within Ethiopia where non-Fairtrade labourers earned 5% below the median wage whereas the ‘Fairtrade’ workers earned 60% below. This highlights an alarming example of unaccounted labour abuse within coffee supply chains that are presented as ‘Fairtrade’.

The issue stems from the Fairtrade Certification, which pays coffee producers who meet certain labour, environmental and production standards an above market ‘Fairtrade’ price. This aims to empower growers, particularly of the Smallholder bracket, to develop ethically and sustainably, whilst ensuring the coffee is of high quality. However, this system is problematic because it requires producer groups to be transparent and accountable when they do not have the incentive to do so. Consumer actions and intentions are relayed through the coffee roasters and importers, which is where the Fairtrade Certification is regulated and awarded. Critics suggest information is collected from voluntary surveys, and such stakeholders do not have the authority or means to ensure a forced labour free supply chain.

Evidence suggests that Fairtrade coffee does successfully assist some Smallholder coffee farmers, but it does not prevent conditions of forced labour or alleviate poverty as it intends. The Fairtrade certification must either be seen as a means for consumers to assist in the reduction of slave labour to work alongside other legal responses to abuses within this industry or it must be adapted and adopted as a centrally regulated certification. Alone, current means to denote a brand ‘Frairtrade’ does not have enough weight to eradicate forced labour from the global coffee supply chain.