As well as the illicit drug trade, Mexico is increasingly known as a global destination for sexual tourism controlled by the organised crime cartels. Beneath this lies systemic issues with sex trafficking and various forms of labour exploitation of adults and children. Despite being a despicable crime, sexual exploitation is seen as a profitable business because “you can only sell a drug once, but you can sell a woman countless times”, quoting Mario Hidalgo Garfias, a convicted human trafficker from Mexico City in 2015.

CASES

Significant cases that have brought the Mexican sex tourism industry to light are the raids in Toluca in November 2017 where 24 foreign women, mostly Venezuelans were released from captivity in a ‘spa’ that offered prostitution. Under similar circumstances, on 30th of July 2020 Mexican Federal Police raids on spas in Cancun and Playa del Carmen freed 21 women (21-25 years old) leading to charges against 12 human traffickers. This case gained media attention due to protests erupting in the aftermath of the raid, which shined light on the chronic issue of impunity in Mexico.

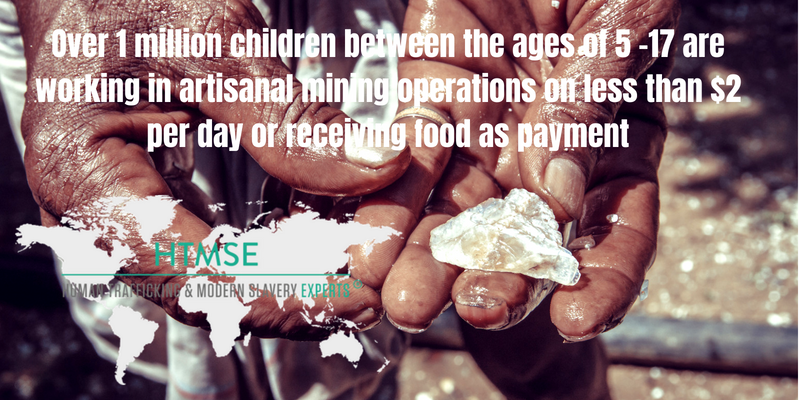

In both cases, these women have traveled to Mexico on tourist visas, under the promise of highly paid legitimate jobs, and then forced into sex work under the threat of violence, fraud, force or control. These control mechanisms of exploitation are also present in other Mexican industries such as agriculture, domestic service, child care, manufacturing, mining, food processing, construction, tourism, begging, and street vending, compromising vulnerable women, children, men and gender fluid people.

Most trafficking victims are migrants from as far as Europe, as well as neighbouring countries in Central and South America, particularly El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and high numbers from Venezuela where ongoing political turmoil makes women and children vulnerable to exploitation. Reports of child sexual exploitation is an increasing problem in northern Mexico, where homeless or orphan children are of high risk, and in several cases parents are complicit in the exploitation of their children. Transgender communities of all ages are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation. The US Department of State reports the users of sexual tourism generally travel from the USA, Canada and Western Europe, and occasionally include Mexican Nationals.

Whilst on vacation, many tourists purchase memorabilia clothing and other items without hesitation from sellers on the beach. HTMSE is alarmed to see the high number of minors being used in the familiar context in conditions that contravenes the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Many minors are being forced into labour, carrying heavy goods in sweltering heats including clothing, coconuts, and food. Many are laden with huge weights of goods, and are being used to attract tourists to purchase these items. These are not conducive conditions for a child. Tourists are fuelling and normalising this practice, whereas in their country of origin it would be illegal, for example in Britain parents could face prosecution.

It is evident that the internet is increasingly used as a vice for trafficking, either via recruitment on social media, or using crypto-currencies to launder payment. This form of contact is used to anonymously set up employment related traps, target victims through false intimate partnerships, or exercise blackmail and coercion through reaching family members of the victims.

ACTION & RESPONSE

In the most recent reporting period of 2021 Mexico lies in tier 2 of the USDOS Trafficking in Persons report, meaning that it does not meet the basic requirements for combatting human trafficking. However, despite the drawback presented by the pandemic, Mexico has increased efforts since the 2020 reporting period.

In 2020 the Mexican state investigated 332 suspected sex trafficking cases, 12 suspected forced labour cases, and 206 unspecified cases of exploitation. There were a total of 75 federal prosecutions of human traffickers, which accounts for approximately half as many as 2019. Unfortunately, this is likely due to the pandemic as federal and state courts suspended all legal proceedings between March and May 2020. This also hampered efforts of authorities to collect evidence from bars, hotels and sex tourism venues, and halted or slowed requests for information to pursue prosecutions, and disrupted intergovernmental collaboration on existing and new investigations.

Positive efforts in the Mexican response to human trafficking included bolstering the Secretariat of Finance’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF) which is a key institution to collect intelligence around trafficking investigations and prosecutions. In July 2020 a cooperation agreement was signed with the National Anti-trafficking Hotline which facilitated the collection of data from calls to trace illicit financial activity connected to trafficking. Flagging several suspicious transactions successfully led to several arrest warrants for human traffickers.

In 2020 the Mexican state provided funding to three victim shelters run by NGOs, but overall their response lacks a victim centred approach. Most states rely on prosecutors to identify and refer victims. State agencies in partnership with NGOs offer medical care, food, and housing in temporary or transitional homes, and other services, such as psychological, and legal services, but this is heavily varied and unavailable in some parts of the country, and often excludes victims or forced labour or male victims of exploitation.

Mexican law provides protection against forced criminality of trafficking victims, however due to issues around formal identification there are potential cases where authorities have detained or jailed victims of trafficking. This includes children involved in gang related criminal activity and migrants in detention facilities, who have been compelled to commit crimes by their traffickers. Furthermore, victims have been withheld justice due to their lack of faith in corrupt authorities and public sector officials.

There is a significant problem of impunity in Mexico which helps to facilitate human trafficking and in turn, the sex tourism industry. The 2019 USDOS Trafficking in Persons report highlights that in at least 17 of the 32 Mexican states, there are alliances between criminal groups and federal, state and local government officials. These officials collude in trafficking crimes such as immigration officials accepting bribes to allow irregular entry of trafficking victims into Mexico, yet in other cases explicitly participate in and run sex trafficking operations. An example of law enforcement abusing their authority for sexual exploitation was seen in the case of human rights activist Karla Jacinto. In 2015 she reported that at 12 years old, she was forced into prostitution for four years and during this period when police turned up at the hotel she was held, they made the customers leave in order to film the girls in compromising positions, and blackmailed the girls into submission by threatening to send the videos to their families. In 2020, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) received 6 claims of trafficking related abuses by public officials. Unlike 2019, there were no prosecutions or convictions of officials in 2020.

HELPLINE & AWARENESS DAY

A significant development in human trafficking response in Mexico is through the binational anti-trafficking hotline set up in 2015 between US’ NGO Polaris and Mexican organisation Consejo Ciudadano based in Mexico City. This collaborative approach encourages citizens to file complaints, and in 2020 reported receiving 1,931 calls related to trafficking, which led to identification of 245 victims, and resulted in 45 investigations. This binational approach is essential for a problem that crosses national borders and involves several jurisdictions.

Furthermore, the “Corazón Azul” or Blue Heart Campaign in Mexico was set up in 2010 in partnership with UNODC which is designed as a ‘pact’ to mobilise social conscience around human trafficking, sexual and other forms of exploitation. It is composed of a set of moral principles for the public to understand and agree to. Annually, buildings are lit up blue to raise awareness. Recently in 2021 there has been significant effort through this campaign to reach indigenous communities who are particularly vulnerable to human trafficking.

BINATIONAL TRAFFICKING HOTLINE: https://contratados.org/es/node/35331

Statistics pulled from the 2021 USDOS Trafficking in Persons Report. For the full report, see here.